‘Last season was the worst season of my career. […] It was the season when I felt so much appreciation for everyone that supported me. And it was because of everyone’s support that I was able to recover in the second half of the season. If it wasn’t for everyone’s support, I may have seriously quit figure skating after Internationaux de France [in Grenoble]. That’s how depressed I was after my short program. I am so grateful! I will do my best in order to be satisfied with my own performance and give back to everyone who helped me by showing that performance. I will give it my all.’

(Source)

’If the thing done was what no one could understand, it was Wakan Tanka. How the world was made is Wakan Tanka. How men used to talk to the animals and birds was Wakan Tanka. Where the spirits and ghosts are is Wakan Tanka. When a man dies, his ‘wanagi’ [spirit] leaves his body. […] Its ‘nagi’ [another spirit] goes with it to show it the way [to the spirit world]. The journey is […] Wakan Tanka.’

(Walker. J.R. Lakota belief and ritual, p. 70-71)

I. 2018-19: Wakan Tanka, Thunderbird, and ritual dances

NHK Trophy, Gala (November 2018)

The Ice, Nagoya (August 2019)

Choreographed by Shae-Lynn Bourne in spring 2018, «Great spirit» attracted a lot of attention and stirred some controversy almost immediately after its first showings, largely on account of its unorthodox musical choice and colorful choreography. The soundtrack was the product of international collaboration between the Dutch DJ Armin van Buuren, another DJ duo from Israel Vini Vici, and the French electronic group Hilight Tribe. The resulting eclectic mixture that includes elements of EDM (electronic dance music), psytrance, and tribal, set against a quasi-ritual textual background in Lakota language, is a truly unique creature in a fairly conservative world of figure skating. Shae-Lynn’s hyper-expressive, very energetic, and almost ‘animalistic’ choreography added to the complex and multifaceted portrait of the program.

Quoting and translating the full lyrics of the song will hardly be of any use, since the text is composed of loosely related words and expressions patched together from the Lakota-English dictionary by the members of Hilight Tribe. The majority of those are of sacred and/or ritual character: ‘Grandfather / Creator’ (tunkasila), sacred ‘Woman/Wife’ (winyan), a person’s spirit ‘nagi’, a ‘tribe / nation’ (oyate) — these are scattered bits that belong to the complex spiritual world of various Lacota tribes. At the center of this mythological system stands ‘Wakan Tanka’ — the ‘great spirit’ or ‘great mystery’, the creator of the earth, whose spiritual power resides in all the animate and inanimate objects: ‘the trees, the grasses, the rivers, the mountains, and all the four-legged animals, and the winged peoples’ (Black Elk in conversation with John Neidhardt). Reproducing this system of beliefs in its entirety and integrity was hardly the point of Hilight Tribe’s compilation. What was clearly more important than the ‘sense’ of the text was its unusual sonority — in other words, the magical and quasi-ritualistic qualities of its sound.

Similarly, Shael-Lynn’s choreography seems more interested in referring to more generic ‘ritualistic’ and quasi-archaic features of the music than specific figures and rituals of the Lakota tribe. At the very beginning of the program, for instance, what attracts our attention is how the skater’s left foot makes several ‘stomping’ moves:

When the same stomping reappears just a few seconds later, now incorporated into a spinning motion of the skater, the allusion to sacred circle dances becomes particularly clear: in the gif below, I compare it to a) the pan-Indian ‘fancy dance’ which became quite popular across different native American tribes and communities in the first half of the 20th century, and b) ’Augurs of spring’ from Nizhinsky’s original rendition of Stravinsky’s ballet ‘The rite of spring’ (subtitled ‘Pictures of pagan Russia’ by the composer himself).

Another image that can be interpreted simultaneously as a universal symbol and a more specific mythical figure appears right after the cantilever, when Shoma raises his arms like wings and starts ‘floating’ in the air (left). This gesture could well refer to a bird-like symbol, probably of an eagle (right), but it may equally well represent the mythical Thunderbird (center) — the creature that appears in multiple myths and legends, including that of Lacota people.

Even further from any specific references, but still within a more generic ritualistic context, are some of the hyper-expressive and quasi-animalistic, almost spasmodic, short bursts produced by skater’s arms and upper body. Their expressivity is particularly striking when seen from a closer distance, as in some fancams:

Some of Shoma’s more prolonged moves, too, including his signature cantilever and the ‘Kevin Aymoz move’ below, reveal the same tortured and twisted bodily expressivity:

The first half of the program gradually builds up to a powerful climax, first approached right before the dramatic musical rest and the ‘drop’, and then finally exploding in the final part, which was later transformed into a full-blown step sequence.

In this section of the program, Shoma’s deliberate use of straight arms, two deep squats in a row (called ‘grand plié’ in ballet, ‘besti squats’ in figure skating), as well as a very energetic spinning motion with a noticeable twist of the upper body — all this points in the direction of contemporary ballet, rather than any ritualistic or sacred dances. The gif below compares one part of this section to Wayne MacGregor’s «Chroma» — curiously, the original source of Kazuki Tomono’s short program choreographed by Philip Mills.

With the ‘drop’ and the final part of the program, there comes a crucial transformation: Shoma no longer looks like a spiritual figure, a shaman or a sacred spirit — he transforms into a pop star and hits a dance floor.

At the end, one should not forget that the entire program takes place not in a sacred wood of a forgotten tribe, and not as a part of an archaic ritual — with it, we find ourselves in a club, on a dance floor. In front of us, we see a DJ mixing his tracks.

Archaic rituals, sacred dances, Thunderbird — it must have been a hallucination of a sort, a vision prompted by a combination of laser light effects and monotonous beats. We see youngsters here, not elderly shamans. And we are dancing — not reading prayers!

II. 2019-20: Smells like… teen spirit?

Japanese Nationals, SP (December 2019)

All signs that reveal first small changes, and then ultimately a complete transformation of the program into a new competitive shape, can be seen in the evolution of Shoma’s costumes.

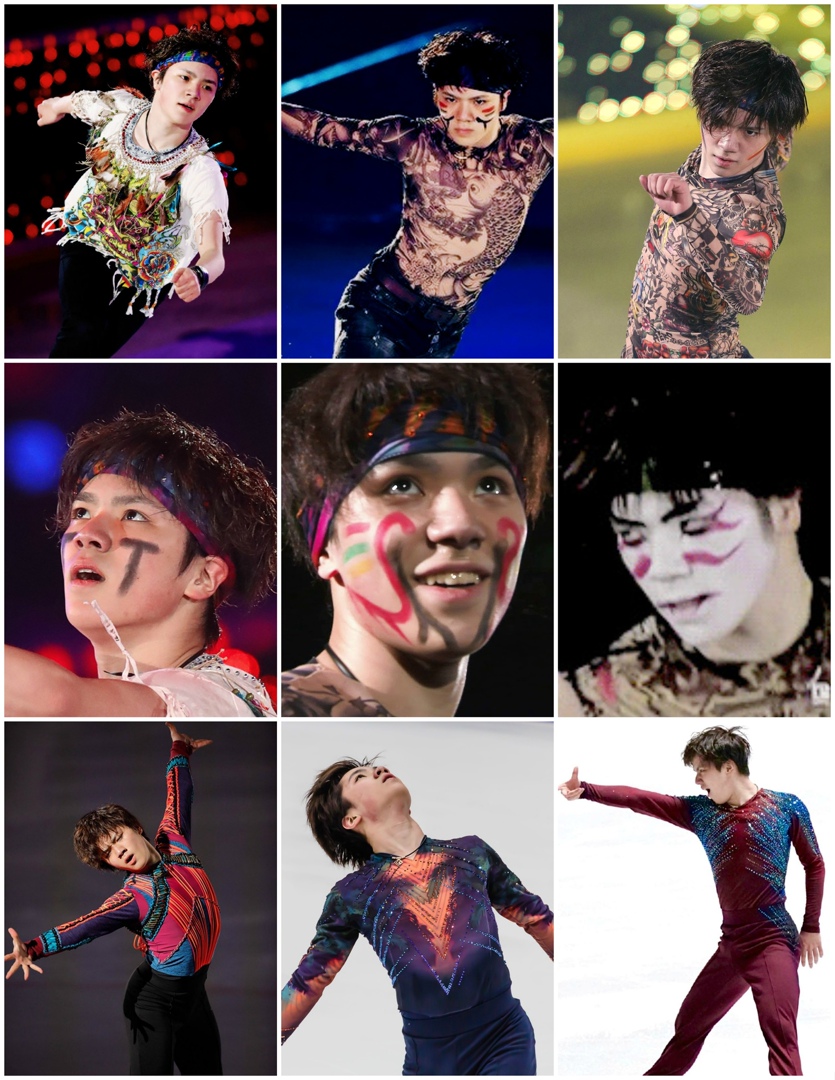

The first, rather eccentric and extremely controversial, one (1st row, left) comes from this program’s premiere in May 2018. Its extensive use of feathers in particular shows a clear reference to a somewhat problematic popular image of ‘Indian’ culture. The two similar, but not identical, shirts that Shoma wore afterwards (1st row, center and right) made a decisive — and very wise — step from dangerously specific allusions to native American culture towards a more generic and eclectic mixture of ritualistic and totemic symbols.

This went hand in hand with some changes in face painting (2nd row), which was usually applied by the skaters present backstage. In these colorful decorations, the one on the right clearly stands out: the juxtaposition it creates between the Japanese kabuki tradition and the tribal and ritualistic features of the program is truly unique, but very much in the eclectic style of this number.

The first costume of the 3rd row (left) — wildly colorful and eccentric — was clearly a temporary solution, and it then gave way to the two masterpieces created by the Canadian designer Mathieu Caron for the reincarnation of this program under a new competitive shape. Both costumes are very elegant, yet simple: the former, to quote the designer himself, was ‘a graphic and modern reinterpretation of foliage at sunset’; the latter nicely juxtaposed the brilliance of Swarowski crystals with an elegant monochrome bordeaux fabric. Here, the past references to native American cultures, totemism, and the kabuki theatre all but disappear, giving way to a new concept, new feelings, and new emotions.

This deep transformation affected the program structurally, both in terms of overall design and specific elements. In the process, some choreographic embellishments had to go. The first segment of the program leading to the quadruple flip is a good example of this: at some point between early November (Cup of Russia) and late December (Nationals 2019), the ‘circle dance’ mentioned above was eliminated from the program. As a result though, the musical structure became even clearer, with the end of its first half accentuated by the besti squat, and the end of the second by the jump itself.

Structurally, all three jumping passes retained their original positions in the short, even though the jumps themselves were substantially upgraded. The central cantilever move was not affected either, which made it the first ‘full’ cantilever ever in Shoma Uno’s short programs (the one in «Ladies in lavender» was considerably shorter and was used as a creative exit from the triple axel, not an independent element). In more practical terms, the inserted cantilever allowed the skater to move his last jumping pass, triple axel, to the second half of the program and get a bonus 10% on top of its base value.

Because of all the technical requirements, both spins from the exhibition became much longer and more complex in competitive program, which means that some of the choreographic moves immediately before and/or after these spins had to be sacrificed in order to accommodate these longer versions. In addition, a combination spin — which is in fact the longest and most complex of all three — had to replace the climactic build-up mentioned earlier. Interestingly though, the two segments still have more in common than one might expect, particularly in their final parts which involve a lot of spinning.

Not unexpectedly, the final part of the program after the drop underwent more drastic changes in the process of its metamorphosis into a step sequence. Still, the resemblance between the two versions is very noticeable: the more recognizable beginning and end of that section (with its butterfly jump and a layback position) remained almost the same, and even in-between there were some common moves, such as a couple of hops followed by a lunge near the end of the step sequence (see the gif below, main screen) — both moves taken from the exhibition program (smaller screen below), even though there they were not consecutive (I made them seem consecutive in the gif only to facilitate the comparison):

Differences are much more substantial, of course. The main structural change was necessitated by the insertion of two obligatory clusters of difficult turns: one near the beginning of the entire section, on the right foot and in counter-clockwise direction,

rocker RFI-RBI; counter RBI-RFI, twizzles (speed slowed down to 0.75)

the other on the left foot and in the opposite (clockwise) direction.

counter LBI-LFI, rocker LFI-LBI, counter LBI-LFI (speed slowed down to 0.75)

Comparing the two different versions of this program, I tended to use the words like ‘sacrificed’, ‘replaced’, ‘disappeared’, and other, as if the process of change was only detrimental to the program’s structure and sense. It is not that straightforward and one-sided, however. There were undoubtedly some losses in this metamorphosis, yes — but some gains as well. First, fewer choreographic moves and elements means there is more space for breathing, both for the skater and his audience, which means there is no need to insert these spaces artificially into the program anymore, as was the case with the exhibition, where Shoma had to stop a couple of times to take his breath. Second, the lighter and less fully packed choreography allowed the skater to regain his signature speed, with the result being that the remaining choreographic elements gained more emphasis and definition. And lastly, all the qualities of the song itself — its boundless youthful energy, its rhythmic drive — came through this thinner choreographic veil in a much more audible and well-defined way. All those qualities that make the audience clap throughout the program and give a standing ovation at its end.

At the end, little was left from the ritualistic and animalistic spirit of the exhibition — the new «Great spirit» finalized its move into a club and onto a dance floor. With this move, it acquired its modern, extremely energetic, and surprisingly youthful look. As well as its powerful impact, and not just on the audience — it has already influenced at least one other athlete beyond the narrow limits of the figure skating world.

III. 2020-21: Thankfulness

A powerful boost of energy that passes from the performer to the audience and then comes back and reaches the performer again — this was exactly what Shoma needed during the tumultuous 2019-20 season. Two performances of «Great spirit» stand at its opposite poles: on the one hand, the disastrous skate in Grenoble which made Shoma seriuosly consider his own retirement; on the other — the inspired skate at the Nationals, after which he could hardly contain his euphoria.

In less than two months that passed between the two competitions, there was a miraculous change within the skater — the change that Shoma himself attributed to the audience’s support in Grenoble. From that moment on, Shoma’s gratefulness has found its expression both in words and deeds. For example, in opening a Youtube channel and using this new platform to share the news and his thoughts on life and figure skating, to show his house and his dogs — in other words, to share the other side of his personality, of who he really is as a person.

Apart from that, Shoma started appearing on all sorts of gaming streams, podcasts, on another Youtube channel opened by his brother Itsuki, and so on — and whenever he had a chance to talk about his life in figure skating, he kept stressing the importance of the support he received, and how it influenced his subsequent decisions. He talked about his gratefulness. All this was completely unimaginable just a few years ago, when all his international supporters had was an extremely old-fashioned website with almost no opportunity for feedback or dialogue, practically unusable for Shoma’s international fan community, as it was in Japanese only.

Last but not least, when Shoma was choosing his new motto for the 2020-21 season, it was this one word that he ultimately picked: ‘thankfulness’. Every single competition, every single skate of this program in 2020-21 is an attempt to show his gratefulness, to give back to his supporters the performance that he himself could be satisfied with.

After all, is it not the most important message of this program: the transformation of the skater and the human being, the coming-of-age story, the process of finding yourself in this life (something David Wilson mentioned in his recent interview), the unbreakable spirit and the newly found desire to compete; the strength to be vulnerable and share your vulnerability with others, particularly with those who support you and care about you? Is it not what ultimately made this program so impactful and so meaningful both for Shoma and his fans?

Perhaps this journey, this internal transformation and the coming-of-age story — all this is also, in its own unique and mysterious way, Wakan Tanka?

Happy birthday, Shoma! And may the great spirit RISE AGAIN!

P.S. I would like to thank @alchemist_irina for graciously granting me the permission to use her artwork in my post.

Woow! Such a wonderful analysis of the program! Thank you for this!

LikeLike

Thank you for this! I noticed that the exhibition and competition versions of the programs felt different, so I appreciate your explanation (and gifs) of exactly what was changed and how that impacted the feel of the program overall.

LikeLike